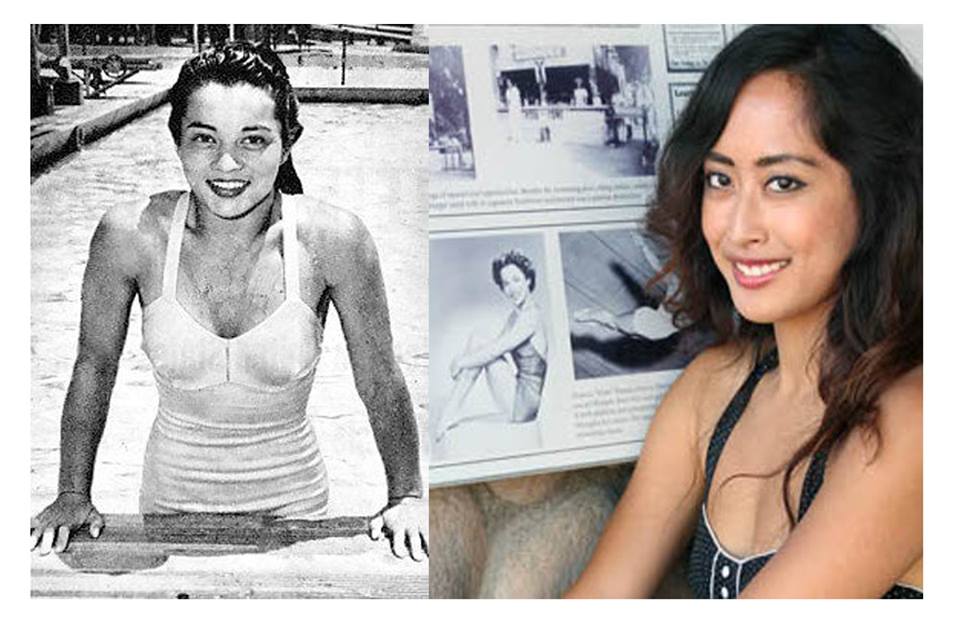

By Georgina Tolentino, guest contributor I first learned of Victoria Manalo Draves when I read her obituary in the New York Times in 2010. The person who handed me the newspaper in a restaurant said, “Wow, you look just like this woman,” and walked away.

I did see the resemblance. She was half-Filipino and English. I was Filipino with a half-Portuguese mother and Italian-Spanish-Native American father.

Victoria was born and raised in San Francisco at a time when her parents couldn’t walk together in public. She grew up when pools were “whites only” facilities and had one dedicated day a month for people of “color” (this also meant immigrants, including Jewish and Italians). This allowed “internationals” to swim before the pool was sanitized for use the next day.

At the 1948 Olympics in London, Victoria Manalo Draves became the first Fil-Am woman to win two gold medals in diving. However, she faced a lot of racial prejudice along the way.

I grew up watching IFC, the Sundance Channel and loving film. I worked for three companies in LA — Maybach and Cunningham, LET Films and Divya Creative — while taking acting classes and auditioning during lunch breaks. Honestly, I got tired of the extremely limiting roles available for women: “cynical hottie #2” or “girl having affair.” I was also tired of being told, “Well, you’re not Asian enough.”

However, I believe that a beautiful shift is happening in independent filmmaking, television and media, which women like Vicki had fought for in their fields. As my passion for telling her story grew, I decided to both produce and play Victoria in an independent narrative film with the help of Brittany del Soldato, Reggie Elzey and what today is Icarus Film Studios.

I started the process of making Vicki’s film by interviewing her husband, Lyle Draves, who also was her coach. I also got in touch with Sammy Lee, coach of diving star Greg Louganis, who was himself a legendary Olympic diver and Korean American icon. Jack Lavery, a friend who introduced her to diving at Fleishhacker saltwater pool in the 1930s in San Francisco, was also helpful. Then Connie, Victoria’s twin sister, shared great stories, like when they sent the same Christmas card to each other by accident.

Sammy Lee recalled that when Vicki first joined the team at the Oakland Athletics, they all wanted to push her into the pool as a hazing prank. But she found out about it, so she covered herself in baby oil. This made everyone else fall into the pool, making everyone laugh and see what a funny person she was. I believe her sunny attitude enabled her to endure the obstacles thrown in her way.

Vicki’s spirit was alive through these people; they are already in their nineties, and yet still joke and tell stories about her, keeping her spirit alive. There is an energy and light in their eyes that can’t be explained. Jack Lavery started laughing, held my hand and said, “Well you have Vicki’s smile – so that’s good.” I was so moved.

When we drove Jack to Sammy Lee’s house, they hugged as old friends, and we became invisible, which made me laugh. Jack had planted a “Sammy Lee plant” in his garden, and after six years finally was able to give it to Sammy. They began talking as if they were back in their twenties. We just watched in amusement, happy to give them that moment.

I have gotten to know Victoria through these friends of hers. The first time I saw a video of her, I started crying because she was no longer a photo. I felt as though I was meeting her in that moment, watching her smiling and winning. I knew what that moment of victory felt like for her, when losing her dad drove her to win in his honor. I really want people to recognize that Vicki fought for both her name and her family’s honor. I only want to do the same.

Preparing for the role has been a commitment. I got a trainer who is amazing and helped me through my back injury, with inversions, building stamina to train the muscles for diving and understanding a diet that improves performance. I go to diving class twice a week in Santa Monica or in Pasadena, and recently started taking private sessions. I also attend ballet class once or twice a week. I’ve begun understanding diving as an “aerial” sport.

When I don’t want to get up at 8 a.m. to dive, I try to remember that when Vicki first dove at the Fairmont Club, they only let her in once she changed her name to Taylor, her mother’s English maiden name. She had a special club where she was the only member. In one competition her father wasn’t allowed into the facility to watch her; so she refused to dive until they let him in.

I didn’t understand why she dove until I started diving. She, like me, had a fear of heights and drowning, ironic for a woman who won gold in 10m and 3m springboard. She dove for her father, for her mother, for the community that accepted her as an equal in sports. She dove for her friends who faced Japanese internment and for women who were being held back. She dove for her English aunt who married a Filipino and faced threats at work because her marriage was deemed “disgusting and wrong;" her aunt was later found dead in an elevator shaft. She dove not for what America was, but for what it could and should become.

Like Vicki, I was also born and raised in San Francisco. I am proud because it is a city full of activists and grassroots movements working to change society for the better. In English, Vicki's maiden name, Manalo, means to win. It's an apt name for a fighter. So, I fight for the rights and opportunities I have -- and for Vicki’s story to be told.

Join me in telling the story of Victoria Manalo Draves. Contributions help us meet our goal of $12,000. Help us build the momentum for a story that needs to be told by being a supporter and by encouraging your friends to do so as well.

You can donate by visiting our campaign here.

Facebook: Vicki Manalo Film Instagram: @vickimanalofilm Twitter: @vickimanalofilm #vickimanalofilm Website: www.victoriamanalofilm.com

Georgina Tolentino is an actor and independent film producer from Los Angeles CA.

The original version of this post originally appeared on Positively Filipino and has been reprinted with permission.

Photo credits: Brittany Del Soldato and Vanessa Cabrillas

While technically not a Pilipino tradition rooted in cultural history (major sky lantern festivals are traditional in Taiwan and Thailand), floating sky lanterns are popularly used in the Philippines to celebrate special occasions or released just for fun. In 2013, the Philippines broke the

While technically not a Pilipino tradition rooted in cultural history (major sky lantern festivals are traditional in Taiwan and Thailand), floating sky lanterns are popularly used in the Philippines to celebrate special occasions or released just for fun. In 2013, the Philippines broke the