In 2014, few days go without comment on the increasing prominence of Hispanics or Latinos in American life. Spanish can be heard in almost every major American city and the Hispanic proportion of the population continues to increase. Census projections point to a future where Latinos will be a plurality or even a majority of Americans. These changes will have huge ramifications on the language, culture, and politics of the United States, many of which are already evident.

As Filipino-Americans also become more prominent in the United States, it’s worth wondering how they will fit into a more Latino, Spanish-speaking America. The Philippines has always occupied a unique position culturally. A mixture of Malay, Chinese, Spanish, and most recently, American cultural influences makes it not entirely at home in either Asia or Latin America. It has been referred to, sometimes negatively, as the “Mexico of Asia.” However, despite similar last names, attitudes, and many times, even physical appearance, there is a distance between Filipinos and Latinos. The biggest stumbling block is language. Though many Spanish loanwords exist in Tagalog and other Philippine languages, very few Filipinos can speak Spanish fluently. Unsurprisingly, Filipinos are literally left out of the conversation as Spanish becomes more important.

This was not always the case. For three centuries, Spanish was the language of law, education, and religion in the Philippines. After the Philippine Revolution and occupation by the United States, Spanish acquired a very negative connotation as the language of a former colonizing power that was backward and primitive. The American colonial government did much to expand English education throughout the archipelago and often compared its mission to the previous Spanish colonizers. Through much of the 20th century, the dominant narrative of Philippine history was that the United States had freed the Philippines from poverty and superstition imposed by Spain. For many Filipinos coming of age in the newly independent republic after 1946, English was modern and versatile, Spanish was archaic and useless.

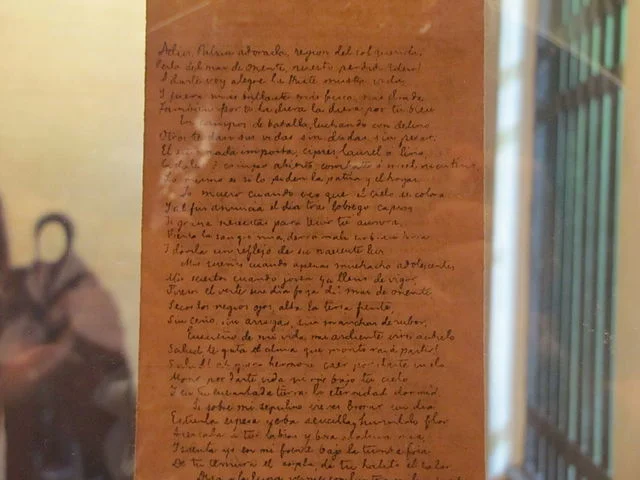

In hindsight, the American-imposed narrative of a backward, Spanish speaking Philippines being replaced by a modern, English speaking one is not entirely correct. If it was the language of its colonizers, Spanish was also the language of the Philippines’ greatest patriots. The works of Jose Rizal, El Filibusterismo and Noli Me Tangere, were written in Spanish. Rizal’s most famous poem, and arguably the most famous poem written by a Filipino, Mi Ultimo Adios, is best read in the original language.

¡Adiós, Patria adorada, región del sol querida, Perla del mar de oriente, nuestro perdido Edén! A darte voy alegre la triste mustia vida, Y fuera más brillante, más fresca, más florida, También por ti la diera, la diera por tu bien.

Indeed, Spanish did not disappear after 1898. It remained the language of education and political activism well into the 1930’s. A speech given by President Manuel L. Quezon can be found on YouTube with two sections, one in English, and the other in Spanish. Unfortunately, war and cultural change made the language all but extinct in the Philippines. The heart of old, Spanish speaking Manila was totally destroyed during the battle for the city in 1945. The liberation of Manila involved enormous loss of life – estimates run into hundreds of thousands killed and many more displaced. Those residents of old Manila had kept their linguistic and cultural traditions alive through four decades of American rule. After the war, there would be few to replace them. At the same time, American pop culture, as communicated by an increasingly powerful mass media, began to influence every aspect of Philippine life. American movies, TV shows, music, sports, and fashion dominated the Philippines after WW II and have continued to since then, with Filipinos watching, listening, and often times discussing them in English. The official status of Spanish ended in 1973 during the government of Ferdinand Marcos. By that time few Filipinos outside of the elderly spoke the language fluently. The change merely reflected reality – Spanish had all but disappeared.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=663otOvJVGU

Filipino-Americans today might ask what if any relevance these events, some more than a century old, have on them in the United States. It’s quite ironic that as the first few generations of Filipinos grew up without any connection to Spanish, the language has gained a new importance. With the Philippines as the call center capital of the world, Spanish speakers are once again in demand, no doubt due to the huge number of Latinos in the American market. In the United States itself, Spanish is becoming indispensable. The present wave of immigrants from Mexico and Central America is the largest in American history and will no doubt permanently alter the United States as a nation.

In retrospect, the decision to end the official status of Spanish as a Philippine language seems myopic and misguided. Of course, Philippine lawmakers in the 1970’s could not have imagined the changes that would take place just decades afterward, namely, the economic emergence of Latin America and the spectacular growth of the Hispanic population in the US. For Filipino-Americans, usually English speaking since birth, this is a unique opportunity to reconnect with identity and gain a very useful skill. A common theme of the Fil-Am experience is the search for identity, of what it truly means to be Filipino despite often not having been born there or not speaking the language. It may seem unusual, but learning Spanish is one step to defining that identity. It is already the most commonly studied foreign language in the US. Learning it and becoming fluent would be of immeasurable help in better understanding and communicating with the already 50 million American Latinos who could be their classmates, neighbors, or coworkers. Most importantly, it would be a bridge to the foundations of Philippine nationhood, the words and works of Rizal, Aguinaldo, Bonifacio, and Quezon. Learning Spanish would improve Filipino-Americans’ understanding of another people’s culture and heritage – as well as their own.

About the author

Cristobal Zarco was born in the Philippines and grew up in New York, specifically Long Island. He graduated with a degree in political science from Adelphi University. He enjoys tracking down books about Philippine history and exploring lesser known parts of New York City.

Cristobal Zarco was born in the Philippines and grew up in New York, specifically Long Island. He graduated with a degree in political science from Adelphi University. He enjoys tracking down books about Philippine history and exploring lesser known parts of New York City.