When I find myself surrounded by female relatives, there is one topic, both beloved and dreaded, that always enters conversation. Once I was with my mom, two aunts, sister, and four girl cousins, waiting in an airport, when the ubiquitous question popped up.

"Do you have a boyfriend?" When the answer was no, there was a follow up question.

"Well, is anyone courting you right now?"

This routine usually generates incredulous reactions from myself and fellow twenty-something year old cousins at the use of the dated word "courting." Come on, Tita, people don't do that these days, we'd explain while scrolling through our iPhone texts.

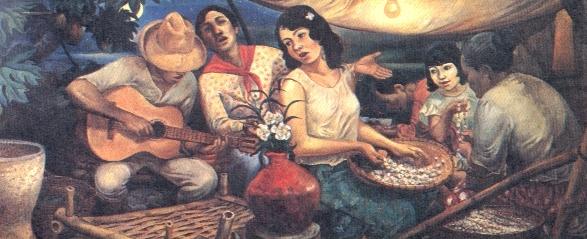

Determined to enlighten us millennials about traditional romancing, my mom and aunts openly reminisced their own stories of courtship in the deep provinces of Bicol, which is where they grew up. They recounted expectations of interested men, as they had to fetch water, cut wood, perform a harana, do farm work, and much more to win over not just a girl, but her whole family.

One particular experience from their stories stuck out, however.

Every year during fiesta season, teens in the town flocked to the town plaza for a dance. One of my aunts admitted to actually sneaking out of the house just to make the event. Ladies put on their best dresses. Men put on cheap cologne and, with no gel available, used vaseline to slick back their hair. My mom said that girls sat in a fenced off area, while men–some visiting from other barangays–raced to approach the most beautiful ones to ask for a dance. The few minutes they swayed, always a conservative distance apart, was their getting-to-know-you phase.

"It was my biggest fear that if I went to the plaza, I'd be a wallflower. No one would pick me to dance with them," my mom said, sounding as worried as she must have been at 17.

"Girls are taught to be timid. But they were really put on a pedestal," she reasoned. My aunts nodded their heads in agreement.

Sheesh, I thought. That is way too much waiting around.

"Sometimes it'd take years before a girl finally gave a pining guy her attention."

Years?

"When you court a girl, it's more valuable if it took you a while. You learn patience... this thing now about 'hooking up' and whatever? OH-MY-G! Ohhh no!" she laughed. My dad sent my mom love letters and poems, and even picked her flowers from the garden.

"That's how it should be, Kristina."

There is something undeniably alluring about this slow-moving game played by lovers in my parents' youth. Anticipation. Innocence. Things that seem scarce in today's world, where Tinder rules the dating sphere. Even the words associated with courtship: manligaw, kilig, ibig, kasintahan, sound undeniably poetic on the tongue. I am romanticizing, however. I know the foundation of my golden-age syndrome (the belief that a past condition is infinitely better than the present) is from a singular experience and antiquated tradition.

In reality, I'd never subscribe to the doctrine of timidness that is essentially imposed upon women, including my mom, from birth (the "Maria Clara" syndrome, if you will). If I like a guy, I let him know, much to my mother's chagrin. However, my mom's stories do make me reflect on love and the state of "courtship" today. How have hearing these stories of my titas and my mom growing up affected how I act around guys and what I expect out of modern day love? Is it completely irrational to wonder if someone will ever serenade me outside my window?

While I already know the answer, I'm just going to lament and leave this song right here.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59jm5_8KqhE

Photo credit: Tagalog SEAsite Project