Author's note: this is the first, of hopefully several, in a series that provides a glimpse of Pilipino communities around the world through my own travel experiences.

Author's note: this is the first, of hopefully several, in a series that provides a glimpse of Pilipino communities around the world through my own travel experiences.

One of my most favorite hobbies out there is to collect stamps. I would travel far and cross countries just to receive an exotic one. I would try to hop around a few nations just so I could help bolster my collection further. Admittedly though, the stamps that I collect aren't ones that you paste into envelopes but are ones that you receive in your passports.

Admittedly, the condition of mine is not at it's best and I've had issues on occasion for it's authenticity (last June I had not one, not two, but five Chinese immigration officers in Shenzen inspect it, much to the annoyance of passengers behind me) but it's almost filled up to the point where I can feel worthy enough to request a replacement. Each stamp inside it can easily evoke memories of trips long past, but there is one that I've valued since receiving it five years ago: the stamp that I received upon entry to Kish Island, Iran. And while the original purpose of my trip was to collect that stamp and say that I visited Iran, I ended up running into a group of overseas Pilipinos who live in legal limbo.

I booked my ticket at a travel agency in the relatively old Bur Dubai district of this otherwise dynamic emirate. An agent greeted me with a "Hello, Kuya. How can I help you?" She is one of the many overseas Filipino workers (OFW) that make up the diverse expatriate population of Dubai - expats make up about 90% of the emirate's population. I proceeded to her desk and joined her friend, a fellow OFW, who was hanging out with her during his break. It was on this day that I made my reservations for a flight to Kish and marks how I found out more of the Filipinos who don't reside, don't work, but wait in that island.

Not wanting to be left behind by the explosive growth going on in the Gulf, the Iranian government designated Kish Island as a free trade zone in hopes of catching some foreign investment flowing into the region. One incentive to encourage growth was that, unlike mainland Iran, Kish didn't have a visa entry requirement. This incentive, however, attracted foreign workers of neighboring countries whose visas were close to expiration. Instead of paying an expensive airfare back to their home countries, they would take a short and cheap flight into Kish, take advantage of the visa waiver, and wait it out until their visas are renewed. Some wait for days, some weeks, and some for months. Ate Travel Agent made sure to emphasize that last point for me when she handed me my ticket:

"Remember, while you may be able to visit for just a day, there are hundreds still waiting to come back to Dubai."

The following morning I found myself in Terminal 2 of Dubai International Airport. Unlike the more glamorous parts of the larger Terminal 1 (along with Terminal 3 which opened after I visited), Terminal 2 was a no-frills building for low-cost carriers and smaller regional carriers that serve destinations I'd typically hear in the news. My most favorite memory out of that place was watching a family with little kids that looked dressed for a day in Disneyland board a flight... to Kabul. The gate of my Kish Island flight was filled with the passengers that make up the demographics of Dubai's working class foreign labor: individuals from Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia were seen. I'd hear dialects that I never heard before, which at times was so overwhelming that I saw comfort when I heard a Tagalog speaker floating in the crowd.

Now the flight itself was the epitome of unconventional. While our boarding passes gave us a designated seat assignment, it was apparently thrown out once we entered the cabin in a Southwest Airlines-esque free-for-all for onboard seat selection. The Fokker 50 we were on board certainly had a colorful history: overhead signage was in English and Spanish while parts had a smattering German thrown in for diversity, a prime example of Persian resilience despite trade embargoes, which prevent the likes of it's local aviation industry from acquiring spare parts.

I ended up sitting next to a young Pilipina who was about to join the kababayans in limbo at Kish. She hailed from Cagayan; she had left the comforts and familiarity of her home in order to provide for her parents by becoming one of the many OFWs in the region. OFWs there are not strangers to the difficulty of adjusting to the culture shock, the backbreaking hours put in, the rights that they had (or rather didn't have), the crowded conditions of living with six other OFWs in a studio apartment, and more. The list goes on.

As we were chatting and I learned more of my seat mate's history, I remembered the words that Ate Travel Agent gave me the day before and I suddenly broke into tears. The epiphany of how realizing much I was blessed with as a Fil-Am became more hard-hitting. It made me realize more how much of a bubble I lived in, more so than from my encounters in the Philippines. Yes, I had heard about other overseas Pilipino communities and occasionally bits on their struggles. But to hear it from themselves was nothing short of powerful.

Now arrival and passport control at Kish was an experience in of itself: as long as the lines were, it nonetheless moved and it moved fast, that is, until I came up. Upon seeing my US passport, I was escorted to the side while the officers took care of the remaining passengers. Eventually, I was all by myself in the immigration hall, growing more concerned, and eventually scared, as the minutes passed. What didn't help was that I was sharing the hall with Iranian soldiers who looked like they were enjoying the fear that I was emanating. Eventually, one of them looked directly at me and hand gestured his index finger, moving it across his neck. I began repeating to myself, "I'm gonna die today, aren't I? Am I going to be the next Robert Levinson?!"

In the end, their shenanigans were in jest, and they eventually came up to me to take a gander at my iPod (which was blasting Return to Innocence to calm my nerves, and whose music video inspired me to do a backtrack on my own life at the same moment) and to pick up a few extra English phrases. Disregarding their dark humor, they ended up being friendlier than most CBP officers I usually have to bear with when returning to the US! I was then ushered to a private room where I was given the Iranian equivalent of CBP's secondary screening. Understandably, it seemed suspicious for an American to stay in Kish for just a day and wanted to verify my intentions before sending me off. WikiTravel didn't exist when I visited but it's Kish entry gives a disclaimer that I wish I had received prior to visiting:

Beware: if you are Western, you may be sternly questioned as to the purpose of your visit.

Eventually I managed to join the rest of the expatriates in the town itself. I wandered around the areas where they would spend their days while waiting to return to their intended workplaces. I heard of a story of two Pilipinas who were unable to have their visas renewed, didn't have enough money for a fare to return to the Philippines, and ended up committing suicide. I never did follow up on it for authenticity, but there was one story that I remember earlier this year where another one did unfortunately choose to take her life.

Before heading back to the airport, I made a tour around the island which can be easily done within just a few hours. As I was inquiring about doing the tour, I noticed a flyer advertising the services in Tagalog, a break from all the Farsi that I was overwhelmed with. The island itself is beautiful, with peaceful beaches, ancient underground aqueducts, and a slower pace for those that want to take a break from the hustle and bustle of Middle Eastern economic growth. But ever since this humbling experience, I'm reminded that it is also an island were many overseas workers still wait for their chance to return to job opportunities in order to provide for their families at homes.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MekvELPcprs

And among those are Pilipinos who are thousands of miles away from home. I only managed to catch a quick glimpse of it, and admittedly it's small compared to what Malou Garcia experienced in her week there, Leah Quilongquilong who spent thirty three days, and the thousands of others who continue to wait in that limbo. Even my own half-brother--estranged until a couple years after my visit--had experienced Kish as an OFW (and admittedly quite frequently which unfortunately raised eyebrows with Israeli immigration officials later on as he went through a land border crossing from Jordan!).

As I shake my head, having to work with Argentina's expanded reciprocal fee, waiting for another passport extension at the local office, or having to make a couple trips down to the Chinese consulate to process my visa, I try to remind myself that such inconveniences are petty compared what the Pilipino community in Kish goes through, alongside the greater struggles of millions of OFWs experience.

Ate Travel Agent's words still echo through my trips, and have helped me appreciate the freedom and ability that I have to travel. I may have been given an extra treatment by Iranian immigration but it pales to what much of the world has to do to get an American visa, and even then entry into the US is not guaranteed, as what was seen with Carina Yonzon Grande who was denied entry in Seattle by CBP after a longhaul flight from Manila and an extensive secondary screening process that made my 30 minute immigration backroom interview made Iranian officers seem like peanuts. (At least the Iranians were polite and courteous, that is with the joke about cutting my head off notwithstanding.) I was able to essentially go in and out of Kish as I pleased whereas many OFWs still hang in that legal limbo, waiting for the day when they can return to their exhausting jobs and providing valuable remittances that make up ten percent of the Philippine GDP.

And this experience is amongst several that I use encourage fellow Americans, Fil-Am and otherwise--to not only express--but also appreciate that same freedom. Hopefully through such appreciation and expression, we can be inspired to help out and become more involved with issues that involve Pilipinos at home, in the Philippines, and in the many communities across the world.

Photo credit (top photo): Gulf News

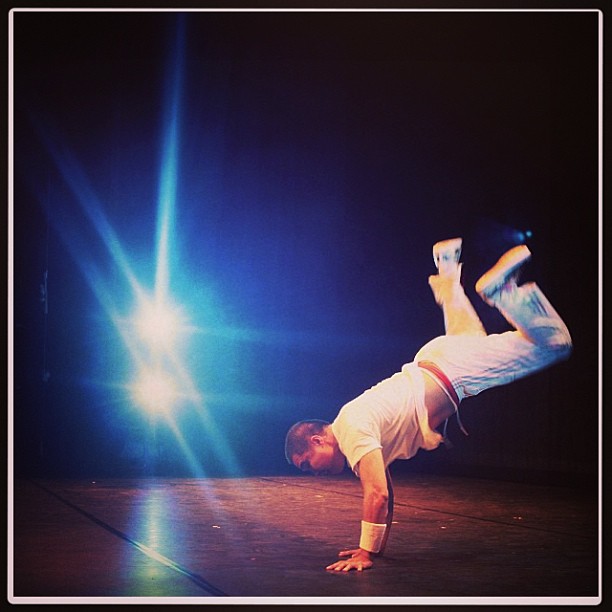

Kilusan Bautista looks as comfortable on stage as others would be in their living rooms. His voice rises up and down in rhythmic acrobatics: flipping sounds into the air, letting stories free fall, catching each word in his natural cadence. He presses the microphone to his lips so that each “p” sound punches the air.

Kilusan Bautista looks as comfortable on stage as others would be in their living rooms. His voice rises up and down in rhythmic acrobatics: flipping sounds into the air, letting stories free fall, catching each word in his natural cadence. He presses the microphone to his lips so that each “p” sound punches the air.