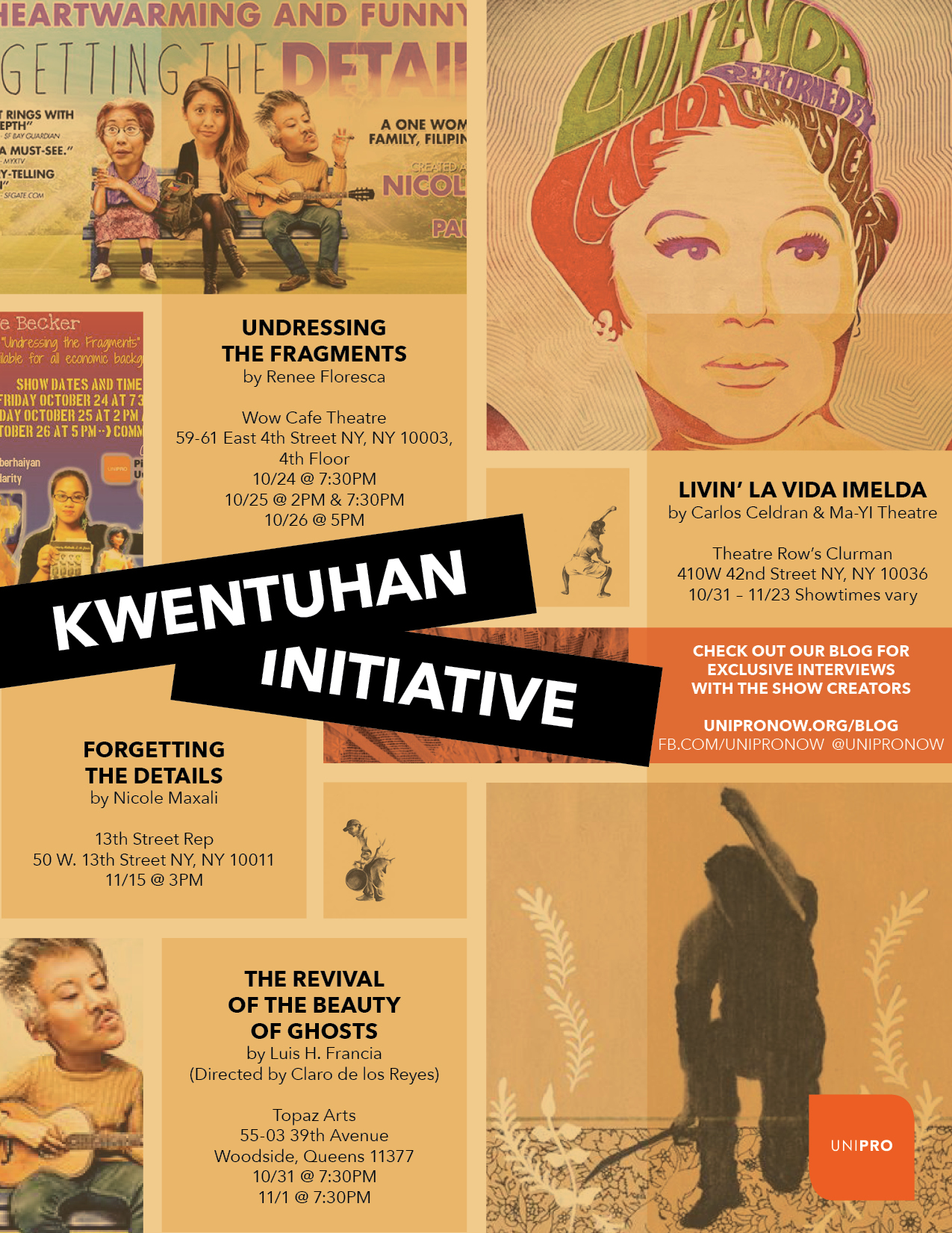

This past October, in honor of Filipino American History Month, we began to promote the stories of our community through an initiative called Kwentuhan. But storytelling shouldn’t end once it’s November 1st. Actor and writer Nicole Maxali shares:

“When I first started acting at the age of fifteen, the only Filipino actress I could look up to was Lea Salonga. And in college, I remember that a college professor wouldn’t let me do my final paper on Asian American actors because, she stated, “There aren’t any to write about!” So much has changed since then. But we still lack positive representation in American TV and Films. Since I began writing and performing as a solo performer/storyteller, my intention is to inspire other Fil-Ams, Filipinos and women of color that our stories are worth writing, performing and watching.

“As Filipinos, it’s not just important to be nurses but to be artists as well. It’s equally important to write and share our stories! I learned years ago that waiting around for Hollywood to write and cast me in a positive Filipino American narrative film was just as fruitless as waiting around for a winning lotto ticket to fall into my lap.

“If I wanted change, I’d have to create it myself! We Filipinos are a hardworking and resourceful people. Just take a look at the first wave of Manongs that immigrated to Hawaii and Delano, California. For decades we have been making our dreams come true in this country, so performing this show to sold out houses and receiving rave reviews proves that we can continue to do so.”

The show Nicole describes is Forgetting the Details, a critically acclaimed tale of a woman torn between tradition and ambition, struggling between her Filipino roots and the American dream. At a recent encore of this one-woman show, an audience gathered to witness Nicole’s talents and to experience the journey of that woman, her father, and her grandmother as they navigate their strained relationships with one another in contemporary San Francisco. Nicole elaborates, “Forgetting the Details has themes that explore a young woman’s Coming of Age, Change versus tradition, Facing Reality, Loss, and Family. The show tells my story of being raised in San Francisco by my traditional Filipino grandmother, yet influenced by my free-spirited father, and the struggles we face as a family when my grandma is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. It's a powerful story that reaches beyond the Filipino American context and touches upon powerful elements of the human experience.”

I had the privilege of being part of that live audience at the cozy 13th Street Repertory in downtown New York, entering with few expectations and leaving floored by the show. Contrary to the show’s title, it seems that no detail is forgotten when it comes to describing the play’s unique characters. Manifesting her unique characters’ complexity through their actions and interactions with one another, Nicole develops her characters with such detail that the show seems set apart from others. As the play goes on, the characters reveal more and more while pulling the audience deeper and deeper into Nicole’s memories. For example, not many can sympathize with Nicole’s father, presented initially as a drugged-up dropout, cast aside by the family in favor of his brother, a college graduate and Navy sailor. We learn later that he, like his daughter, is an artist. He is a dreamer with a childlike wonder, lost in his music and painting, and seeking the acceptance from his daughter that he never gained from the rest of his family.

View the Forgetting the Details trailer.

True to life, Nicole’s characters also display a wide range of emotions as they embark on journeys of transformation throughout the course of the play. The characters express depth and complexity during every interaction, each moment strung into a chain of poignant and real memories. For example, while Nicole was once ashamed of her grandmother’s brazen personality, she learns to appreciate her grandmother’s wit and sage advice, adoring her as they grow older.

Similarly, the show itself has come a long way since its inception eight years ago. Nicole explains:

“I started writing this piece in 2006 during a solo performance workshop I was taking taught by W. Kamau Bell (Host of the FX show “Totally Biased”). During that year, my grandma was diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. It was a difficult time for my family and for me, especially since my grandma provided unconditional love and stability during my formative years. So I chose to write about it in Kamau’s workshop. Writing was my coping mechanism--a positive outlet for the pain. After our class final, Kamau told me that it was some of the best writing he has ever seen me perform.

“The piece evolved as I performed it in venues around San Francisco. Soon people began approaching me, sharing their own stories about loved ones with Alzheimer’s. They related to this story in a special way due to their experiences with Alzheimer’s. I realized that my show had become something more than just a source of healing for me. It was a way for people to connect to a piece that was both real and funny. And it spoke to their own issues of caregiving, guilt, shame, mental health, and family dynamics. My desire to add to healing and light in an otherwise dark and painful world of Alzheimer’s disease was my source of inspiration.

“The first time I performed the full-length version was November 2011…just four months after a close family member passed away. It was a very challenging time for me but I continued with the West Coast premiere of my show at Bindlestiff Studio in San Francisco and sold out most of my shows and received rave reviews and standing ovations.

“Since 2011, it’s become a tighter and stronger show. Originally 100 minutes, I have since then cut it down to a 75-80 minute show. I’ve also injected more humor to it. My background is also stand-up and improvisational comedy. So performing this show for the past three years in different cities around America (Boston, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, etc.) has led me to find new jokes within the show. And working with my director, Paul Stein, for the past four years has definitely shaped the show to what it is today.”

Her grandmother’s declining health becomes a focal point in the play, as her sickness becomes a burden for Nicole and her father. Not every father-daughter relationship runs smoothly, and their relationship is no exception. Both characters struggle between their dreams and their responsibilities, often delving too deep into their trade while familial obligations come second. However, the further and further Nicole distances herself from her father as time goes on, the closer and closer her father comes to returning to her life, especially as a result of her grandmother’s illness. The importance of their relationship eventually climaxes during her father’s death, when Nicole discovers just how proud her father was of her from the newspaper clippings he saved about her, even during years of separation.

Forgetting the Details is simply a play I will not forget. Nicole states:

“I want the audience to walk away with a greater appreciation of their lolas, parents, family, and the loved ones around them. Life in general can be stressful and all consuming. But when we take a step back and appreciate the people in our lives that have shaped who we are, it allows us to slow down and take stock of how much we’ve accomplished with their help. Alzheimer ’s disease in general has taught me to stay present and appreciate the people in my life that love and support me. So go call your lola and lolo right now and tell them ‘Mahal kita’!

“Specifically for Fil-Ams, my show touches on the conflict of being a good traditional Filipino granddaughter versus a third generational Fil-Am with her own American dreams. Most Caucasian Americans don’t fully understand the pressure we face in Asian families of being the model daughter/son or granddaughter/grandson. And the pressures we face to take care of our elders as we get older and having our families remain our top priority. It is difficult to find that balance and especially hard to manage the internal guilt we feel if we pick our own happiness or career over our parents’ wishes.”

I, too, had a grandmother who passed away from various complications, a difficult time when my parents also separated. Audience members will feel as if Nicole is telling their stories, and not only hers. Forgetting the Details is more than a tale of a daughter and her grandmother, told with laughter and drama and everything in between; it’s an invitation to Nicole’s dinner table, her heart, her memories, her story as a Filipina American, and her own human experience.

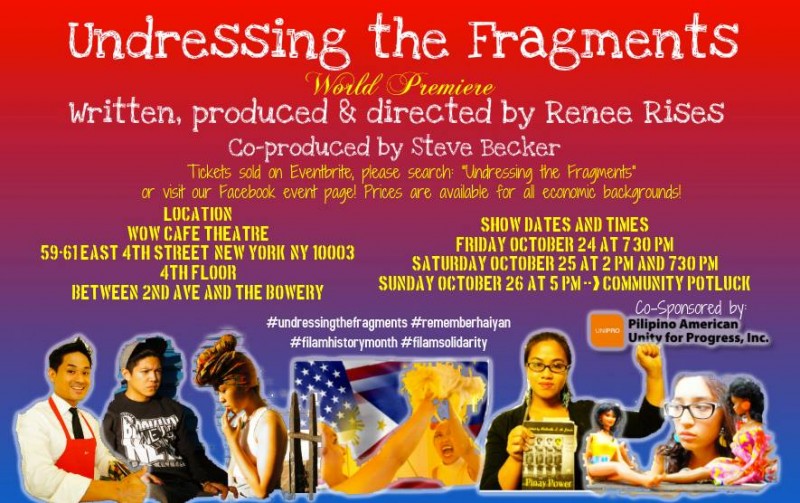

For more Kwentuhan, read our reviews and exclusive interviews for Renee Rises’ Undressing the Fragments and Carlos Celdran’s Livin’ La Vida Imelda. Interested in storytelling within the Filipino American community? Contact us: eboard@unipronow.org

Kilusan Bautista looks as comfortable on stage as others would be in their living rooms. His voice rises up and down in rhythmic acrobatics: flipping sounds into the air, letting stories free fall, catching each word in his natural cadence. He presses the microphone to his lips so that each “p” sound punches the air.

Kilusan Bautista looks as comfortable on stage as others would be in their living rooms. His voice rises up and down in rhythmic acrobatics: flipping sounds into the air, letting stories free fall, catching each word in his natural cadence. He presses the microphone to his lips so that each “p” sound punches the air.