The plight of an oppressed Muslim minority from Myanmar, the Rohingya people, has made headlines worldwide recently. After months of floating across South East Asia, they have found temporary safe haven in the Philippines. The decision to take in the Rohingya was met with international approval, as other Asian nations refused to allow them entry. The case of the Rohingya is not the first time South East Asia faced a refugee crisis.

April 30 2015 marked forty years since the fall of Saigon. After communist victory in the Vietnam War, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese and other Indochinese people left their homes. Hoping to escape repressive regimes, they took to sea in small boats and braved a harrowing journey across the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. Storms, thirst, hunger, and pirates were just a few of the dangers they had to face. “Thuyền nhân”, or boat people in Vietnamese, would become a concern for a generation of South East Asian diplomats and policy makers. The flow of refugees began with just a trickle in 1975, with few choosing to leave Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia so soon after the end of the war. The number fleeing the region increased dramatically each year afterward as economic depression deepened and political persecution intensified. The peak was in 1979, with nearly a quarter of a million refugees fleeing Vietnam during that year alone. Many were ethnic Chinese who became targets for revenge due to China’s 1979 invasion of Vietnam. Refugees continued to flee Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia for neighboring countries throughout the 1980’s, with the flow only stopping completely in 1994. By then, economic growth and political reforms in Vietnam had made it far less likely for people to leave the country.

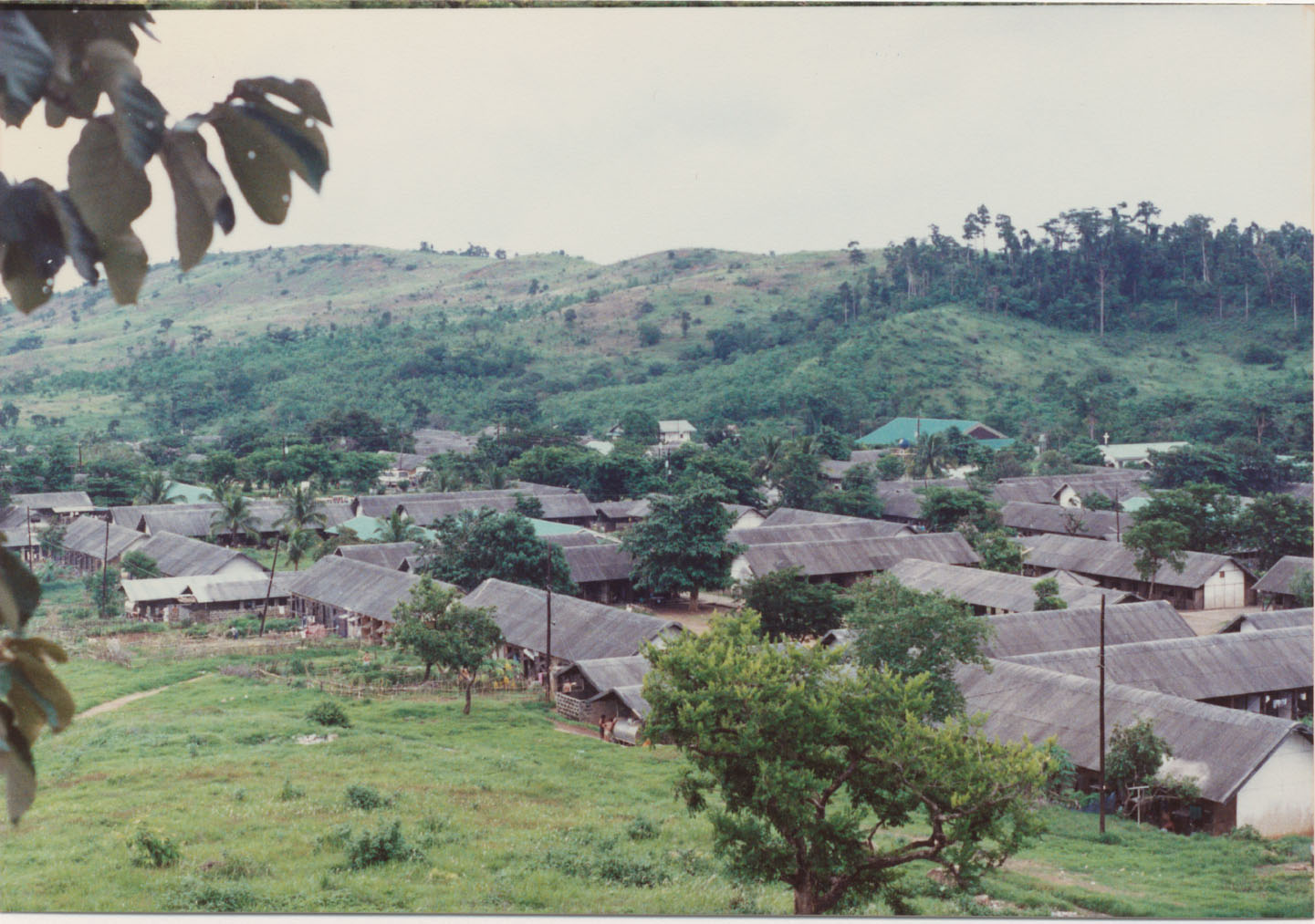

While the Philippines was not the destination for the majority of the refugees, around 200,000 Vietnamese, Lao, and Cambodians were processed by the two main centers in Morong, Bataan, and Puerto Princesa in Palawan. Boat people rescued by the Philippine Navy or Coast Guard would be taken to either of the two where they would stay until they were resettled permanently in other countries, with the United States the destination of choice. Many of the refugees suffered in diplomatic and political limbo, having no documentation or citizenship in the countries they wanted to resettle. As their immigration status and resettlement arrangements were handled, they lived and worked in the refugee centers. The term refugee camp brings to mind nightmarish images of tent cities teeming with disease and despair. Thankfully, the facilities in the Philippines were nothing of the sort. The main center in Morong and Vietville in Palawan were like pieces of Vietnam transplanted to the Philippines. Social services from a range of organizations, religious, governmental, and international, helped the boat people rebuild their lives and provide a semblance of normalcy. The Philippine government provided the land on which the centers were constructed and also guaranteed their security. International groups, primarily the UN High Commission on Refugees and the Red Cross, provided the funding.

Sadly, the treatment the boat people received in the Philippines was not the norm across the region. In Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Indonesia, they were often crammed into crowded and unsanitary camps. Singapore took the hardest line against refugees. The Singaporean Navy was ordered to intercept any boats and tow them out of Singapore’s territorial waters, regardless of the condition of the passengers or the seaworthiness of their vessels. The late Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew was unapologetic about this policy, stating in November 1978 – “You’ve got to grow calluses on your heart or you just bleed to death… Can I afford to have people festering away in refugee camps, being hawked around to countries which are supposed to have compassion for long suffering humanity?” Undoubtedly, these actions led to the death of many boat people whose vessels sank before they could reach safe haven elsewhere. To some degree, Singapore’s policy was understandable. Hong Kong and Singapore in particular had little space or resources to devote to potentially hundreds of thousands of refugees. The Philippines, an entire archipelago and several large islands, could afford to be more generous with space.

Yet the situation in the Philippines was far from ideal when it hosted the boat people. The late 70’s and early 80’s saw economic stagnation and increasing domestic turmoil. The EDSA revolution and the end of the Marcos regime in 1986 only brought a new set of challenges. The economy was in free fall and military coups against the new, democratic government of Corazon Aquino made an already unstable situation worse. The insult “the sick man of Asia” was never more truly applied to the Philippines than during the late 70’s and 80’s. Despite these challenges, the Philippine government addressed the refugee problem with surprising wisdom and humanity. By 1996, the centers in Morong and Palawan were closed, with the overwhelming majority of refugees resettled in the United States and other developed countries.

Philippine policy makers faced a difficult dilemma concerning the boat people. They had to balance national interests against the undeniable suffering of a people in need. To this day, the Philippines is not a rich country and much of its still growing population suffers from grinding poverty and inequality. These problems were even more acute in the 1980’s. Filipinos had to endure power shortages, military coups, and an economy that seemed to only get worse. The fact that the Philippine government managed to find a pragmatic and humane solution to the refugee crisis is all the more remarkable considering these difficulties. Vietnamese refugees in the United States expressed their gratitude in November 2013, collecting nearly 2 million dollars in disaster relief after Typhoon Yolanda devastated the Visayas. It is a high compliment to a nation’s warmth and hospitality when even its refugee camps are remembered fondly. Today, the Philippines and Vietnam work together in resolving territorial disputes in the South China Sea against Chinese expansion. The saga of the boat people proved that despite great hardship of its own, the Philippines could be a safe haven for those most in need.

About the author

Cristobal Zarco was born in the Philippines and grew up in New York, specifically Long Island. He graduated with a degree in political science from Adelphi University. He enjoys tracking down books about Philippine history and exploring lesser known parts of New York City.

Cristobal Zarco was born in the Philippines and grew up in New York, specifically Long Island. He graduated with a degree in political science from Adelphi University. He enjoys tracking down books about Philippine history and exploring lesser known parts of New York City.