Note from the Editor: Jedric Martin is one of UniPro’s interns for the fall. As part of Fil-Am History Month, interns explored California’s new law to include history on Fil-Am farm workers and their efforts in the state’s education curriculum. Read on to see Jedric's thoughts on labor leader, Larry Itliong.

By Jedric Martin, guest contributor

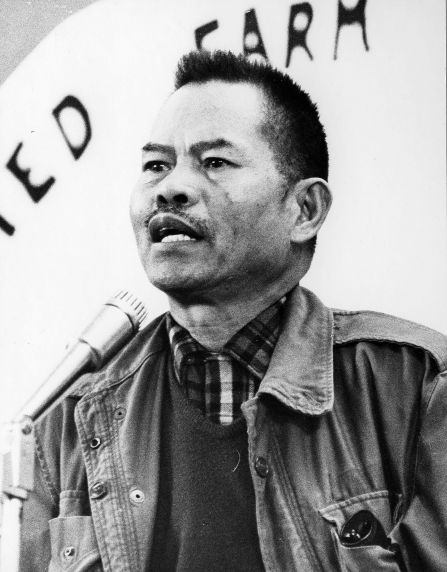

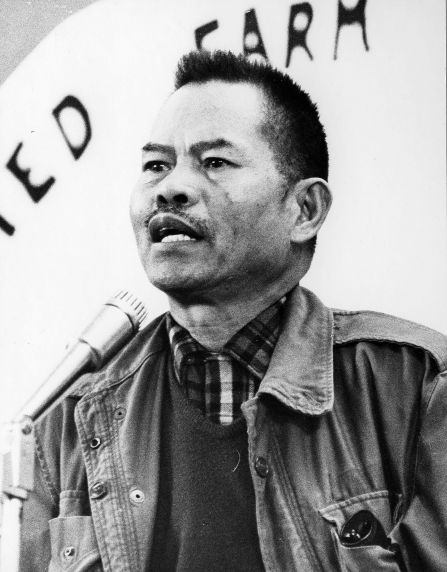

Larry Itliong was a Fil-Am labor organizer. He is best known for leading the Delano Grape Strike, which started on September 8, 1965 and lasted for more than half a decade. Because of his efforts in this strike, he is often regarded as “one of the fathers of the West Coast labor movement.”

Itliong was born to Artemio and Francesca Itliong on October 25, 1913 in the Pangasinan Province of the Philippines. He was one of six children and only had a sixth grade education. Nonetheless, Itliong excelled as an activist, and by 1929, he had immigrated to the United States. One year later, at the age of seventeen, he was involved in his first activist movement: the lettuce strike at Monroe, Washington. Furthermore, Itliong was a very good card player and a regular cigar smoker. He was multilingual, being able to speak fluently in various Pilipino dialects, Spanish, Cantonese, and Japanese. He also taught himself about law, which aided him as both an activist and a leader.

As a farmworker, Itliong was well traveled on the West Coast, having worked in Alaska, Washington, and all around California. Additionally, he worked in Montana and South Dakota. While in Alaska, he helped found the Alaska Cannery Workers Union. Commonly referred to as "Seven Fingers," he received his nickname after losing three fingers in an accident while working in Alaska.

Itliong’s credentials demonstrate his value not only to the Pilipino community, but the American community as well. In the 1930s and ‘40s, Californian Pilipinos led the way in unionization efforts among farmworkers. After serving as a mess man on a U.S. Army transport ship during World War II, Itliong moved to Stockton, California where he participated in the first major agriculture strike to take place after the war. He also served as a first shop steward of International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 37 in Seattle, being elected as its vice-president in 1953.

In 1965, Itliong became a leader of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a union that consisted mostly of Filipinos who immigrated to the U.S. during the 1930s. It was around this time that Itliong, along with Philip Vera Cruz, Benjamin Gines, and Pete Velasco, led a strike against growers of table grapes in California in an attempt to increase their revenue stream to minimum wage. This boycott, which would later be referred to as the Delano Grape Strike, was a very significant victory for Itliong and his fellow leaders, who eventually won higher wages. AWOC would soon merge with the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) led by Cesar Chavez, to create the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Itliong was initially skeptical about the merge, fearing that Mexicans would dominate the union. Nonetheless, Itliong did not share these thoughts, and instead, worked harder to move up in the union. He was a member of the founding board for California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), which was a plan enacted through President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty policy. This plan was initiated in 1966 as a nonprofit legal services program. The CRLA seeks to provide California residents—especially those greatly affected by poverty—with free legal assistance, as well as access to many different education and outreach programs.

Itliong served as the Assistant Director of the UFW under Chavez until 1970; at this time, he was appointed to National Boycott Coordinator. In 1971, however, Itliong resigned from the UFW due to disagreements about how the union should be run. Moreover, Itliong also believed the union did not support aging Pilipinos. Despite his resignation, Itliong still supported the UFW’s cause. He helped organize a strike against the Safeway supermarkets in 1974 and worked towards building a retirement facility for UFW workers, which would later be known as “Agbayani Village.” On February 8, 1977, Itliong died of Lou Gehrig’s disease at the age of 63. Los Angeles County decided in 2011 to give public recognition to Itliong, making his birthday, October 25, an official holiday.

As Fil-Ams, it is our responsibility to acknowledge Itliong’s impact on the Farm Labor movement. The contributions he made may not have affected us directly, but they surely stand as a significant example of how anyone could fight for an important cause, despite having to deal with difficult circumstances. His commitment to UFW’s mission, despite a lack of agreement between him and the governing body of the union, demonstrates not only his strong leadership qualities, but also his good will. The decision of California Governor Jerry Brown to include the contributions of Fil-Ams, such as Itliong, in the academic curriculum of the state is monumental, and it will ensure that these courageous Pilipinos are remembered for their integral role in the Farm Labor movement.

Photo Credit: Reuther Library