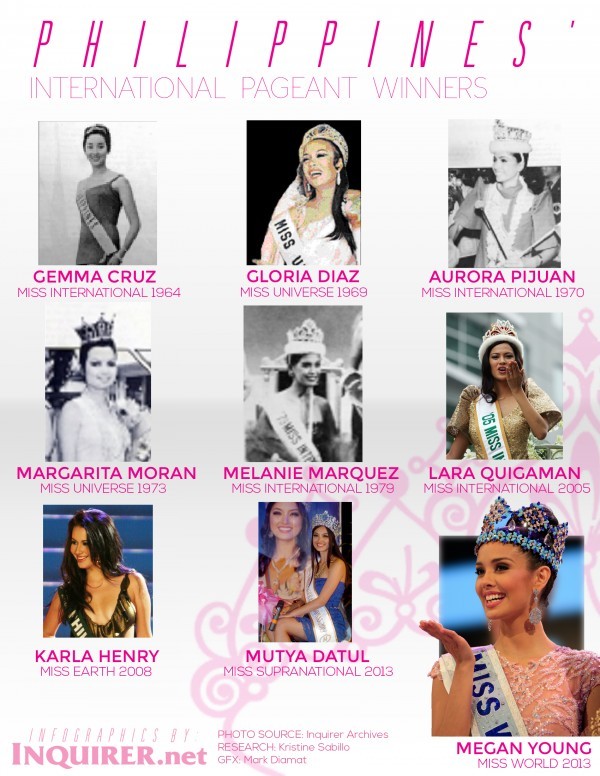

Pilipinos love winning - blame it on having always been stuck in the shadows of their big (pronounced "imperialistic") brothers. So when competitions like Miss Universe and American Idol are on, you can most certainly find Pilipinos tuned in, clapping at their TV screens and speed-texting their votes (although on any other day, most parents magically forget how to use a cellphone). They love rooting for who they perceive to be the “perpetual underdog,” because when the Pilipino underdog wins, all Pilipinos win too -- and it’s sure to be plastered all over Facebook and shared with coworkers at lunch the next day. Sure, it takes skill to compete. But in a world where some competitions can be based solely on audience support (even Miss Philippines advanced to the Top 16 via an online vote in last year’s Miss Universe), how could Pilipinos push a young Pilipino figure skater at the Winter Olympics to victory?

They couldn’t. Because this time, their underdog was alone, relying only on his sheer skill and talent in a sport that practically none of his countrymen dare to try.

Before even stepping onto the ice at Sochi, seventeen-year-old Michael Christian Martinez had already been considered a winner in his own right. He is the first figure skater ever from a Southeast Asian country to participate in the Winter Olympics and the lone athlete to represent the Philippines in only its fourth showing ever at the Games. Could this be the year that a Pilipino figure skater might finally earn a spot on the podium?

SPOILER ALERT:

The answer is no. At the end of the Men's Short Program, Martinez’s score was enough to qualify him for a shot at a medal in the Men's Free Skating Program, but he finished 19th overall. There was no “losing” and certainly no “failing” here; he simply just didn’t get a medal. While a medal might have been what viewers equated to a victory, skating at the Olympics in itself was what Martinez considered the real prize, especially given his humble beginnings in a tropical country without snow.

By chasing his dream, he has opened doors for other Pilipino figure skaters and has reintroduced the Philippines to the rest of the world as resilient and mighty, especially in the wake of Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), along with other storms.

In 2005, at the age of eight, Martinez laced up after being mesmerized by ice skaters at a shopping mall. Nearly ten years later, he would be setting foot on Olympic ice as the youngest skater in the program. Despite suffering from asthma, Martinez’s natural talent for figure skating became apparent and eventually he entered the circuit, winning medal after medal in competitions all over the world. Soon enough, he had his sights set on the Olympics. The passion and talent were there, but the funds unfortunately were not.

Martinez is a modern-day Cinderella man. His family struggled to support his training. His skates weren’t always made of the best quality. His Olympic coaches based in the United States cost a fortune. He wasn’t able to put in the ideal number of hours it took to properly train, because without a dedicated rink in the Philippines, he often had to share space with the public. There was no financial aid available to him from the government. Yet through it all, Martinez persevered and would often turn to prayer, even imploring his Facebook fans to pray for him just hours before his turn in Sochi.

This young boy may not have a medal to show for his efforts, but instead he has the satisfaction of a dream realized to elevate him higher than any podium ever could. By chasing his dream, he has opened doors for other Pilipino figure skaters and has reintroduced the Philippines to the rest of the world as resilient and mighty, especially in the wake of Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), along with other storms.

Martinez is slated to compete again in the 2018 Winter Olympics. By then, he will be more mature, more experienced, more confident... and maybe even flanked by a lot more fellow athletes from the Philippines. Perhaps he’ll even win a medal, and viewers will witness a victory based on precision, not popularity. A victory that is his, and not theirs.

Photo credit: EPA

Photo Credit: The Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, Binibining Pilipinas, Khaleej Times, Filipiknow.net, and amywillerton.blogspot.com

Photo Credit: The Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, Binibining Pilipinas, Khaleej Times, Filipiknow.net, and amywillerton.blogspot.com